On December 22, 2017 President Trump signed in to law the tax reform bill that was the most sweeping and comprehensive overhaul of the tax code since 1986. There were a lot of international provisions that were detrimental to companies doing business abroad but from a US / domestic perspective, the tax changes were favorable and it will change the landscape on the tax rates and how companies conduct business in the US vs abroad.

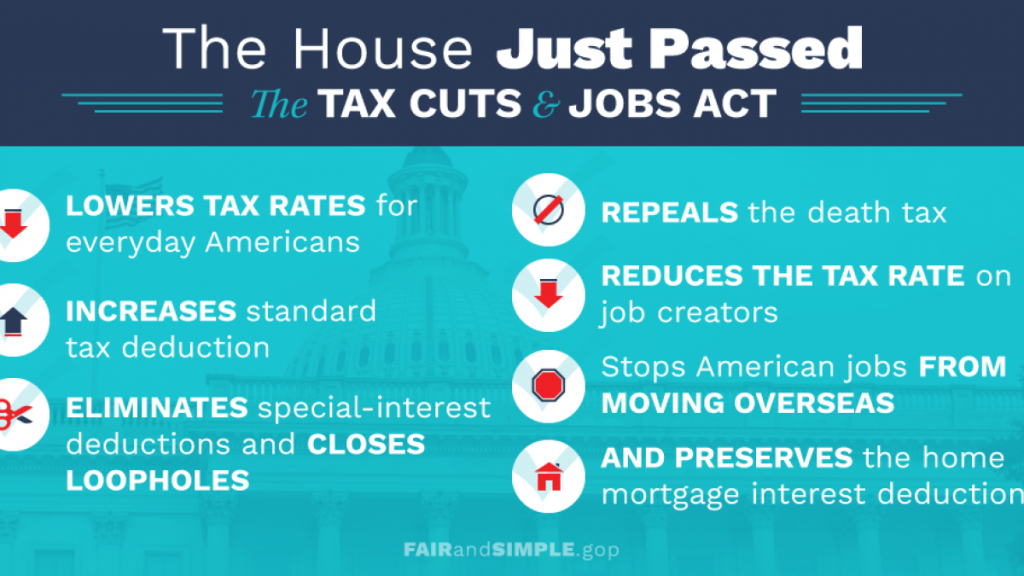

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act which is what it’s called, effective January 1, 2018, the US corporate tax rate dropped from 34% down to 21%. And when I say corporations, I refer to what we call C-corporations. In the US there are three types of corporations: LLC, C and S. These would be the C corporations that experienced this tax reduction. There’s a rumor that it might drop down to 20% in October, when new legislation is tabled so if you take in to consideration the federal rate of 20% and an average US state rate of between 3-5%, you’re looking at an all-in tax rate of 25 – 27%. It used to be 40-41% which is 35% plus a state rate of 5-6% and it was the highest among the OECD nations. From the highest it’s dropped to just below the average, and just behind Canada’s all-in rate which is just about 26.4%.

These tax cuts also have another benefit. In the United States, corporations did not enjoy favorable tax rates for capital gains. Capital gains were taxed at whatever the regular tax rate was. So if it was 40% or 35%, now with the drop in the rate to 21% capital gains are taxed at a much lower rate which makes it much more favorable to purchase and dispose of assets within the corporate solution or corporate structure. It also brings it more in line with the Canadian tax rates.

We’re not suggestion for a moment that the US has become a tax haven, but it has changed the landscape and made their rates more competitive. It has removed the incentive of setting up US corporations by foreign companies doing business in the US. It’s leveled the playing field and it’s also taken away Canada’s long standing competitive advantage with respect to tax rates. 40% vs 26% is a significant difference. When the tax rates were high, most Canadian businesses when expanding in to the US, they tried to avoid US taxation and continued carrying on business as a branch operation. Then if they structured things properly, they would be able to avoid US tax under the Canada / US tax treaty because they didn’t have what is called “a permanent establishment” in the US. Now that’s changing. What we’re seeing is Canadian companies expanding in to the US, setting up US C-corporations and using that as their US base right from the beginning. There is no more branch model. They are a corporation from day one. There are some advantages to that.

Given the current climate in the US with President Trump and the trade war that is developing, setting up a US corporation as a store front is more favorably received by US customers. They prefer to deal with a US corporation. They can see who they can sue. From that perspective, it’s very preferential vs carrying on business as a branch. Having a US corporation eliminates a lot of the cross-border paperwork and I can’t emphasize enough that a lot of our clients who are Canadian and selling to the US are having to fill out what are called W8 forms. They are very, very difficult to complete, very comprehensive and very cumbersome. Having a US corporation eliminates all of that paperwork because with a W8 regime, the law states that every US person paying a foreign person, whether it’s for the purchase of a product or services, has to hold back 30% of the payment. The way to get out of this 30% holding is to provide the W8 form to the US customer.

One thing I want to emphasize, and this is a big mistake that many clients make, is that they believe that filing a W8 form is sufficient: it’s not. You have to also file a US tax return and the type of US tax return that you file depends on the type of W8 form that you prepare and send to your client. Most clients have a W8 BBNE form that is submitted to their customers and this requires the Canadian company to file a protected US return. What you’re doing is relying on the Canada / US tax treaty and saying to the US customer, don’t withhold the 30% payment to me because we don’t have a permanent establishment in the US and we don’t have a sufficient connection to the US market, and we’re not subject to US taxation. That protected return has to be filed. If it’s not filed on time, and this means within 2 years of when it should be filed, the IRS has the ability to step in and impose the 30% penalty tax on gross revenue. If a Canadian client has been selling in to the US at, for example, $10 million/year and they have not filed this treaty-based return, the US can come in and impose a tax liability of $3 million on that gross amount. It’s a lot to keep in mind and monitor. It’s easy to miss these filings so setting up a US corporation just eliminates a lot of that hassle.

The other thing to consider is that having a US corporation lends itself to bringing in US partners. Inevitably it seems that when you expand in to the US, if a US party is interested in purchasing the operations or they want to come in and partner, then it’s easier to bring in a US partner at the US corporate level. Or even down below if you set up at the LLC’s level, you can compare that to introducing a US partner at the Canadian level, it makes it very cumbersome to crossing the border twice and it’s very difficult to structure the organization when you have this type of structure or ownership.

From a next strategy perspective, it’s a lot easier to sell the shares of a US corporation than shares of a Canadian company. Under the Canada / US tax treaty, a Canadian company can sell shares of a US company and not pay any US tax on that capital gain. Article 13 of the Canada /US tax treaty provides that protection. That is a great way to exit the US market with any US tax. On that point, some rules of thumb still hold true. You do not want to set up your US business as an LLC, a limited liability company. These entities are still considered to be hybrids and are treated as corporations for Canadian tax and as pass through for US tax and what that does is it creates a mismatch of foreign tax credits and a double taxation situation. If you do choose to expand in to the US, C-corporations are always the first one to choose.

Another area that the tax reform has impacted is typically Canadian companies that have been carrying on business in the US through partnerships. It used to be that you could sell your partnership interests and not have to pay any US tax. The tax reform has now stopped that. If you sell your US partnership interest, you’re going to pay US tax. Compare that to the sale of US corporation shares of a Canadian parent.

I want to turn, finally, to the sales tax issue in the Supreme Court case. Let’s consider the scenario where a Canadian corporation that sells furniture in to the US market and you don’t have any connection in to the US, do you have to collect US sales tax? Under the old rules, you would not have to collect US sales tax because you did not have a physical presence in the US. This Supreme Court case, and this is not a state Supreme Court, it’s a federal Supreme Court case, now says that you don’t have to have a physical presence in the state for the requirement of sales tax to be collected. Canadian companies now have to look at this new landscape and determine whether or not they have to collect US sales tax because it’s moved from a physical presence to an economic presence.

So, what does this mean? There’s been a lot in the literature about whether or not states can collect sales tax from Canadian corporations. If you wanted to go by the letter of the law, there’s nothing that allows them to enforce collection in an international domain. There’s no tax treaty but I think the right thing to do is very clear. There is a bright line that sales tax should be collected if you have an economic presence in the United States. There are a lot of states now that are revamping their legislation to replicate what is going on in South Dakota, which is where the Supreme Court case took place.

written by Joseph Sardella, US Tax Services